indefinite article, the form of an used before consonants, mid-12c., a weakened form of Old English an "one" (see an). The disappearance of the -n- before consonants was mostly complete by mid-14c. After c. 1600 the -n- also began to vanish before words beginning with a sounded -h-; it still is retained by many writers before unaccented syllables in h- or (e)u- but is now no longer normally spoken as such. The -n- also lingered (especially in southern England dialect) before -w- and -y- through 15c.

It also is used before nouns of singular number and a few plural nouns when few or great many is interposed.

"a hermaphrodite," mid-12c., from Medieval Latin androgyne (fem.), from Greek androgynos "a hermaphrodite, a woman-man" (see androgynous). Related: Androgynism.

mid-12c., cocken, cokken, "to fight, quarrel," probably from cock (n.1). Attested by 1570s as "to swagger," 1640s as "to raise or draw back the hammer or cock of a gun or pistol as a preliminary to firing."

The seeming contradictory senses of "turn or stand up, turn to one side" (as in cock one's ear), c. 1600, and "bend" (1898) are from the two different cock nouns. The first is probably in reference to the posture of the bird's head or tail, the second to the firearm position.

To cock one's hat carries the notion of "defiant boastfulness." But a cocked hat (1670s) is merely one with a turned-up brim, such as military and naval officers wore on full dress occasions.

To go off half-cocked in the figurative sense "speak or act too hastily" (1833) is in allusion to firearms going off unexpectedly when supposedly secure; half-cocked in a literal sense "with the cock lifted to the first catch, at which position the trigger does not act" is recorded by 1750. In 1770 it was noted as a synonym for "drunk."

mid-12c., "large group of people," from Old French compagnie "society, friendship, intimacy; body of soldiers" (12c.), from Late Latin companio, literally "bread fellow, messmate," from Latin com "with, together" (see com-) + panis "bread," from PIE root *pa- "to feed." Abbreviation co. dates from 1670s.

Meaning "companionship, consort of persons one with another, intimate association" is from late 13c. Meaning "person or persons associated with another in any way" is from c. 1300. In Middle English the word also could mean "sexual union, intercourse" (c. 1300).

From late 14c. as "a number of persons united to perform or carry out anything jointly," which developed a commercial sense of "business association" by 1550s, the word having been used in reference to trade guilds from late 14c. Meaning "subdivision of an infantry regiment" (in 19c. usually 60 to 100 men, commanded by a captain) is from c. 1400.

Meaning "person or persons with whom one voluntarily associates" is from c. 1600; phrase keep company "consort" is from 1560s (bear company in the same sense is from c. 1300). Expression two's company "two persons are just right" (for conversation, etc.), is attested from 1849; the following line varies: but three is none (or not), 1849; three's trumpery (1864); three's a crowd (1856).

mid-12c., adopted in Anglo-French for "the wife of an earl," from Medieval Latin cometissa, fem. of Latin comes "count" (see count (n.1)). Also used to translate continental titles equivalent to the fem. of earl.

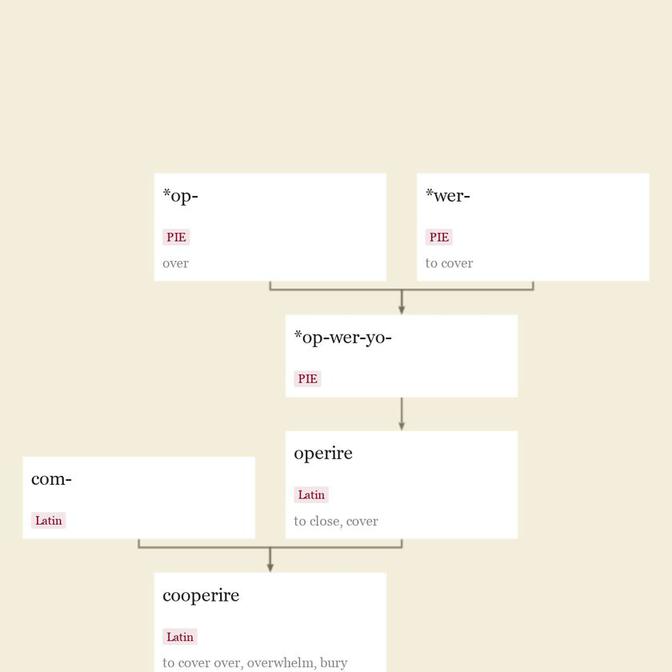

mid-12c., "protect or defend from harm," from Old French covrir "to cover, protect, conceal, dissemble" (12c., Modern French couvrir), from Late Latin coperire, from Latin cooperire "to cover over, overwhelm, bury," from assimilated form of com-, here perhaps an intensive prefix (see com-), + operire "to close, cover," from PIE compound *op-wer-yo-, from *op- "over" (see epi-) + root *wer- (4) "to cover."

Sense of "to hide or screen" is from c. 1300, that of "to put something over (something else)" is from early 14c. Sense of "spread (something) over the entire extent of a surface" is from late 14c. Military sense of "aim at" is from 1680s; newspaper sense first recorded 1893; use in U.S. football dates from 1907. Betting sense "place a coin of equal value on another" is by 1857. Of a horse or other large male animal, as a euphemism for "copulate with" it dates from 1530s.

Meaning "to include, embrace, comprehend" is by 1868. Meaning "to pass or travel over, move through" is from 1818. Sense of "be equal to, be of the same extent or amount, compensate for" is by 1828. Sense of "take charge of in place of an absent colleague" is attested by 1970.

mid-12c., crafti, "skillful, clever, learned," from Old English cræftig "strong, powerful," later "skillful, ingenious," acquiring after c. 1200 a bad sense of "cunning, sly, skillful in scheming," the main modern sense (but through 15c. also "skillfully done or made; intelligent, learned; artful, scientific"); see craft (n.) + -y (2). Perhaps to retain a distinctly positive sense, Middle English also used craftious as "skillful, artistic" (mid-15c.). Related: Craftily; craftiness.

member of an irregular monastic order of priests in the Middle Ages in the Celtic lands of the British Isles, mid-12c., from Old Irish céle de "anchorite," from cele "associate, companion," sometimes "servant" (compare ceilidh) + de "of God." Perhaps an attempt to translate Servus Dei or some other Latin term for "religious hermit." Related: Culdean.

mid-12c., dien, deighen, of sentient beings, "to cease to live," possibly from Old Danish døja or Old Norse deyja "to die, pass away," both from Proto-Germanic *dawjan (source also of Old Frisian deja "to kill," Old Saxon doian, Old High German touwen, Gothic diwans "mortal"), from PIE root *dheu- (3) "to pass away, die, become senseless" (source also of Old Irish dith "end, death," Old Church Slavonic daviti, Russian davit' "to choke, suffer").

It has been speculated that Old English had *diegan, from the same source, but it is not in any of the surviving texts and the preferred words were steorfan (see starve), sweltan (see swelter), wesan dead ("become dead"), also forðgan and other euphemisms.

Languages usually don't borrow words from abroad for central life experiences, but "die" words are an exception; they often are hidden or changed euphemistically out of superstitious dread. A Dutch euphemism translates as "to give the pipe to Maarten."

Regularly spelled dege through 15c., and still pronounced "dee" by some in Lancashire and Scotland. Of plants, "become devitalized, wither," late 14c.; in a general sense of "come to an end" from mid-13c. Meaning "be consumed with a great longing or yearning" (as in dying to go) is colloquial, from 1709. Used figuratively (of sounds, etc.) from 1580s; to die away "diminish gradually" is from 1670s. To die down "subside" is by 1834. Related: Died; dies.

To die out "become extinct" is from 1865. To die game "preserve a bold, resolute, and defiant spirit to the end" (especially of one facing the gallows) is from 1793. Phrase never say die "don't give up or in" is by 1822; the earliest contexts are in sailors' jargon.

"Never look so cloudy about it messmate," the latter continued in an unmoved tone—"Cheer up man, the rope is not twisted for your neck yet. Jack's alive; who's for a row? Never say die while there's a shot in the locker. Whup;" [Gerald Griffin, "Card Drawing," 1842]